How often do you hear people say

And many would feel that from our day to day experience this is absolutely true. In his presentation to the world economic forum Justin Trudeau summed up the feeling of many

“Think about it: The pace of change has never been this fast, yet it will never be this slow again. There’s an enormous opportunity, and enormous potential, in that realisation. Technology has always brought such promise – a better standard of living, new innovations, remarkable products. Consider that progression from steam power, to electricity, to computers. But it also brings dramatic shifts in our social, economic, and political cultures. Workers, people who aren’t seeing the benefits of economic growth, regular men and women who are trying to grab a rung on the career ladder (never mind climb it) – for them, technology is a benefit to their lives, but a threat to their jobs. Over the past few years, we’ve seen the ripple effects of economic uncertainty and inequality play out around the world. The unrest we’ve witnessed is driven by anxiety and fear.”

On the other hand, Larry Summers (University Professor and President Emeritus at Harvard University) talks about a new era of secular stagnation to rival the great depression, a period in which society (companies and governments) lack the confidence to invest new ideas and so reducing capital investment and productivity growth.

The concept of Secular stagnation was originally put forward in 1938 by the Harvard economist Alvin Hansen in response to the Great Depression. He argued that America’s economy was suffering from a lack of investment opportunities linked to waning technological innovation; and not enough new workers due to an ageing population, too little immigration, and the closing of the old economic frontier in the American West.

But from a historical perspective is this true that the rate of change is increasing. Is change now faster than it was in the Industrial Revolution or during the IT transformation that swept many organisations in the latter part of the last century? Or to set it context during the rise and fall of the growth of The Roman empire. What is the evidence for this rate of change, other than our personal perspective? What measures would we expect to see if the change was more rapid than in the past? What would be the indicators of change and transformation in society?

How can these two perspectives be both be true? People feel the pressure of ever-increasing change but at the same time, economists say we are in an era of stagnation. Let’s look at the evidence.

Productivity Growth over two-and-a-half centuries.

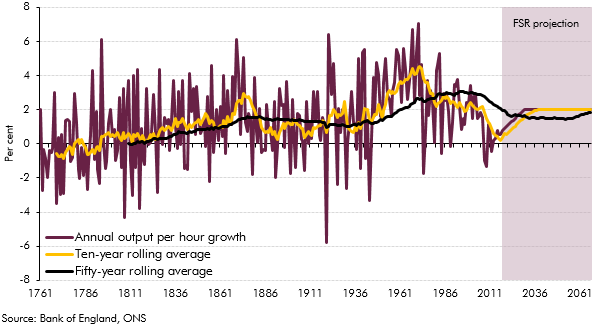

The chart below shows, produced by the office for Office for Budget Responsibility shows productivity growth over the past two and a half centuries. This measures the annual output per hour average worked, so the value generated by each hours work.

We can see two peaks in the 1860’s during the industrial revolution. This included

- The increased use of steam engines in factories and the Railways

- The growth of financial capitalism (investment funded by shares) and international capital markets.

- The development of modern accounting practices.

- Repeal of the Corn Laws abolishing import tariffs and global free trade in food

Inevitably this boom was followed by a long depression between 1873 and 1913.

The next peak is in the “golden age” 1950’s to the late 1990’s. Changes during this period included

- The construction of the first motorways.

- Chain stores and shopping centres.

- The dramatic rise in the average standard of living, with a 40% rise in average real wages from 1950 to 1965.

- Two weeks’ holiday with pay for employees.

- The invention of the transistor, silicon chip and the computer and the associated transformation in business practices.

- Cracking to convert crude oil into petroleum and the growing use of the internal combustion engine and cars.

- The jet engine and international aviation.

- Electricity, the National Grid and domestic electric appliances.

- Modern pharmaceutical industry.

- New materials such as plastic, aluminium and synthetic materials.

- The vast increase in agricultural production and yield from the use of synthetic fertilisers.

- Reinforced concrete leading to skyscrapers.

- Space communications, fibre optics and the internet.

We can see the rate that the rate of productivity improvement came to an end with the late-2000s financial problems. By this measure, the rate of change has slowed dramatically. For example, the first iPhone was launched in 2007 and Facebook in 2004.

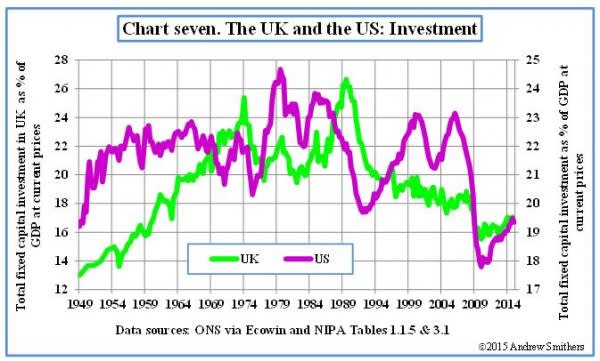

Capital Investment

Another measure of change is capital investment by companies and governments in new ideas. These ranges from new infrastructure projects, factories to build new products or IT systems. Again the charts below from showing a decline in capital investment. Society (companies and governments) is putting less money into new ideas. The Financial Times has published some interesting graphs.

Even more worryingly the return from that capital investment is declining. So for each pound invested society is getting less return. It’s getting harder and harder to find ideas that will generate a return.

In summary, this article concludes that

Low investment, combined with low efficiency presents a discouraging picture. It is possible that the fall in capital efficiency will be reversed and investment will rise but, if this does not happen, the trend growth of GDP looks low enough to reduce the rate at which living standards rise.

This means that with the current rates of investment and productivity growth people are unlikely to experience an increase in living standards.

The Change Paradox.

So we see a paradox.

A world in which people feel that the world is changing, but we feel that as individuals we are not benefiting from these changes.

In previous periods change has to lead to an overall improvement in productivity, overall living standards, profits for companies and benefits for society in general. However the rates of investment have fallen, increases in productivity have reduced. So why do we feel like change is increasing. It may be that people welcome positive change, the introduction of the motorway, modern pharmaceuticals or international travel and do not feel threated by these changes; especially if they are accompanied by an improvement in living standards. But when changes do not lead to an improvement in living standards then people are not so welcoming, people feel threatened, more vulnerable and uncertain. They perceive change as a threat and not an opportunity. It may be that we are on the epoch of the third industrial revolution, driven by AI and big data. And that this will stimulate significant investment and considerable increases in living standards, but the evidence is not there yet to support the line that “The pace of change has never been this fast”

Paul Naybour

Paul Naybour

0 Comments Leave a comment